Historical Notes: Grateful to Mrs. Thurber →

By Majda Kallab Whitaker

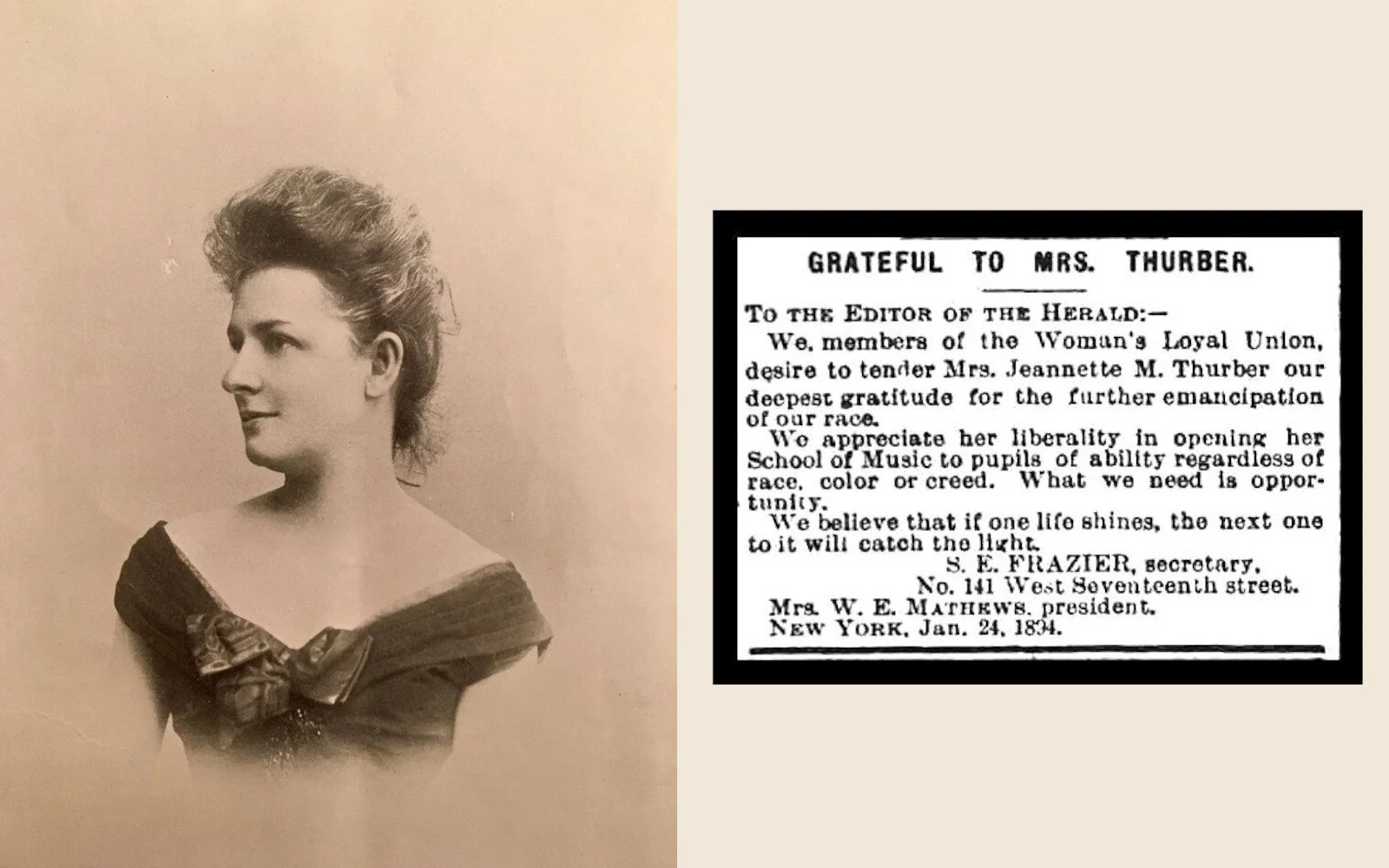

In marking the centennial of women’s voting rights, DAHA highlights trailblazer Jeannette Meyer Thurber, Founder and President of the National Conservatory of Music of America in New York City.

Illustrated American, August 4, 1894

In the 1890s New York progressives were taking action to encourage the advancement of women and to bring about social justice. One of the protagonists was Jeannette Meyer Thurber, founder and president of the National Conservatory of Music of America, a leading and highly influential institution for music study which, in 1885, offered admission to persons of ability regardless of race, gender, creed or physical disability. From its inception the school attracted a diverse student body that was remarkable for the time. In 1892 Thurber, in perhaps her best known act as president, offered the position of director of the Conservatory to Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, thus opening an important chapter in the development of an American (read national) school of music composition, one of Thurber’s visions for the institution. Inspired in part by the diverse milieu existing at the New York Conservatory, Dvořák composed his world renowned Symphony No. 9 in E minor, “From the New World,” which premiered in December 1893 with the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall, and he publicly gave recognition to the importance of African American and Native American musical traditions.

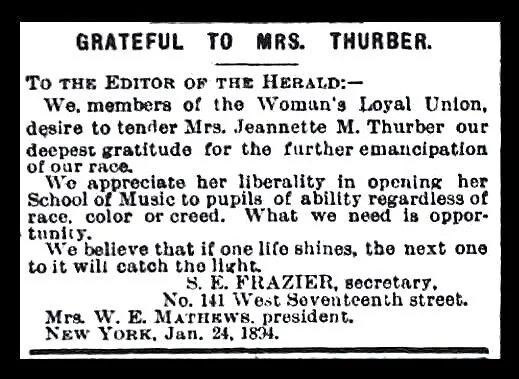

In this context a short but significant Letter to the Editor was published in the New York Herald on January 27, 1894, expressing gratitude to Thurber for her leadership at the Conservatory. The letter appeared four days after an unprecedented concert featuring predominantly Black musicians conducted by Dvořák, which was organized by Thurber for the benefit of the Herald Free Clothing Fund. The letter’s signators commended Thurber for her contributions to “the further emancipation of our race” and for the “liberality” of her admissions policy. They pointed to the need for “opportunity,” which Thurber offered at a time when exclusion of African Americans was the unfortunate norm.

New York Herald, January 27, 1894

The Women’s Loyal Union and the leaders who signed the statement were of historic importance as part of the growing movement of African American women’s organizations. The group was founded just two years earlier, in direct response to the anti-lynching speech given by Black journalist and racial justice crusader Ida B. Wells at Lyric Hall in New York. In addition to raising funds to publish Wells’s speech and seeking racial justice, the organization’s agenda included self-empowerment and voting rights for Black women. The activist leaders, President Susan Elizabeth Frazier and Secretary Victoria Earle Matthews, had personal histories that demonstrated their ability to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles to their advancement, rising above slavery, poverty, and discrimination to find professions in education, journalism, and literary writing. The Conservatory’s opportunities were of course open to all with proven talent, scholarships included. One of the beneficiaries of the inclusive admissions policy was African American singer and composer Harry T. Burleigh, a student befriended by Dvořák, who developed a successful musical career.

News of the Thurber-organized concert, which evidently prompted publication of the letter, appeared in the January 24th issue of the Herald under the headline “Dvořák Leads for the Fund.” The event took place at Madison Square Garden Concert Hall on the preceding evening; featured in the performance were the Conservatory’s approximately 50-member student orchestra under the direction of Dvořák, accompanied by an all-Black, 130-person choir and soloists Sissieretta Jones, a professional soprano who broke color barriers, and student baritone Harry Burleigh. One of Dvořák’s talented composition students, Maurice Arnold, of African American heritage, was invited to conduct his own work, comprising a series of four American Plantation Dances. The overflowing audience included members of the African American community as well as New York society, and the Herald’s extensive illustrated coverage captured the excitement of the occasion.

It was a groundbreaking event both musically and culturally, planned by Thurber to bring attention to her progressive Conservatory programs and projects. The opening sentence of the Herald’s article acknowledged the collaborative nature of the event, stating: “Honor to Mrs. Jeannette M. Thurber, to Dr. Antonín Dvořák and to the students of the National Conservatory of Music.” Near the top of the published list of attendees, filled with Conservatory supporters, the name of Reverend Dr. Parkhurst stands out. The well known Minister of the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church, Rev. Charles Henry Parkhurst was an influential reformer close to Thurber and her husband; later that year he gathered a list of 3,000 names from citizens of New York for an anti-lynching petition presented to Congress by the Women’s Loyal Union, joining others from across the country in seeking a resolution to investigate the violence against Blacks.

Thurber, with the support of Dvořák and her Board of Directors, enacted other measures, including the establishment of a program to train African American students for careers in music education. The initiative created a stir when announced to the press in May 1893, in the period of transatlantic debate about Dvořák’s new symphony and his statements regarding the significance of non-traditional music sources, which were perceived as radical at the time. These were bold steps, though by today’s measure might appear limited in scope. In the 1890s, with integration still an elusive goal, Thurber was nevertheless well ahead of her contemporaries in seeking solutions to unresolved issues emanating from the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the increasingly devastating Jim Crow laws in the South. As the Women’s Loyal Union recognized in their letter, Thurber and her colleagues at the Conservatory were implementing constructive measures, for which the organization expressed deep gratitude. Their letter ended with the hopeful assertion: “We believe if one life shines, the next one to it will catch the light.” That sentiment still stands, over 125 years later, as the nation confronts many of the same issues.

By Majda Kallab Whitaker, cultural historian, DAHA Board Member

Biographical Reference: Maurice Arnold (1865-1933); Harry T. Burleigh (1866-1949); Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904); Susan Elizabeth Frazier (1864-1924); Sissieretta Jones (1868-1933); Victoria Earle Matthews (1861-1924); Rev. Charles H. Parkhurst (1842-1933); Jeannette Meyer Thurber (1850-1946); Ida B. Wells (1862-1931)

Read full article HERE