The Premiere of Dvořák's Symphony

The National Conservatory of Music of America was represented in full force at the brilliant Carnegie Hall premiere of Dvořák's Symphony "From the New World" on December 16, 1893. Dvořák, his wife, and their two sons, Antonin and Otakar, sat in a box of honor with Maurice Arnold (Strathotte), the student composer for whom Dvořák had the highest hopes. Mr. and Mrs. Thurber, Dvořák's American patrons, sat proudly in an equally prominent box nearby. Victor Herbert led the cello section of the New York Philharmonic on the stage below. Scattered in the balconies were other students: Harry T. Burleigh, who had copied some of the orchestra parts on the stands of the players; and a fifteen-year-old cornetist, Edwin Franko Goldman (the future composer and director of his own "Goldman" band), who had already played some of the music from the symphony when he tested the trumpet passages for Dvořák as he was orchestrating, to see if they sat well on the instrument.

The English horn solo made a lasting impression on Maurice Arnold and two of his fellow composition students, Harvey Worthington Loomis and William Arms Fisher. Dvořák had described the slow movement as "a study or sketch for a longer work, either a cantata or an opera ... based on Longfellow's 'Hiawatha.'" But how do we explain that thirty or so years later, just when the copyright was running out, Loomis, Arnold, and Fisher, independent of one another, fitted the English-horn tune from the Largo of the symphony with a "Negro spiritual" text and had it published. Arnold came up with "Mother Mine" and Loomis with "Massa Dear," but it was Fisher's adaptation using his own text "Goin' Home" that eventually established itself as a popular Negro "spiritual." This has to be more than coincidence. It is reasonable to imagine Dvořák's telling members of his composition class that the English horn solo (a baritone instrument not unlike Burleigh's voice) was conceived as a wordless Negro spiritual for Hiawatha!

As for his other composition students at the National Conservatory, three in particular had notable careers: Rubin Goldmark, grandson of a Hebrew cantor and nephew of the celebrated Viennese composer Karl Goldmark; the already mentioned Maurice Arnold, Dvořák's "favorite"; and proud, feisty Will Marion Cook, a man ahead of his time.

Starting in 1924, Rubin Goldmark (1872-1936) headed the composition department at the Institute of Musical Art and its successor, the Juilliard School, holding the post until his death. Goldmark also founded the Bohemian Musical Society. In the winter of 1917, a Brooklyn-born teenager, Aaron Copland, began studying privately with him, a relationship that lasted until Copland left for Paris four years later and began work with his new teacher, Nadia Boulanger. George Gershwin, forever in pursuit of a conservatory equivalency diploma, came to Goldmark for a short period in 1923. Both Copland and Gershwin lauded their work with Goldmark.

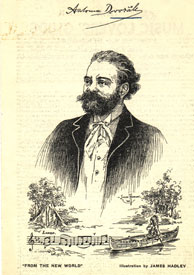

"From the New World" Illustration Photo courtesy of New York Public Library.

Many musicologists have been intrigued by Will Marion Cook, a catalytic figure, an angel of black music who seems to show up for a short yet efficacious time at every notable African American music event from the 1890's to World War II, from Dvořák to Duke Ellington. Cook enjoyed a significant Broadway theater career starting with Clorindy the first all-black musical on Broadway, and climaxing with In Dahomey, which was moved to London for a celebrated run at the Shaftsbury Theater. In 1918 he organized the Southern Syncopated Orchestra, a jazz orchestra with a large string contingent that anticipated Paul Whiteman's hybrid orchestras by almost a decade. The Syncopators also sang spirituals a cappella. In the spring of 1919, Cook and his orchestra set out on a European tour, introducing the newest American jazz styles, with Sidney Bechet as the leading soloist. The Syncopators opened at the Royal Philharmonic Hall, impressing the Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet - "the astonishing perfection, the superb taste, the fervor of its playing" - and garnered a second command performance for Cook at Buckingham Palace featuring Bechet and members of the Southern Syncopated Orchestra.

It was the conservatory-trained Cook and his association with symphonic music that was on Ellington's mind when he was preparing for his first appearance in Carnegie Hall: "[Cook] was a brief but strong influence. ... Some of the things he used to tell me I never got a chance to use until ... I wrote the tone poem, 'Black, Brown and Beige.'" Cook seems to have anticipated Ellington, having once declared: "There will one day come a black Beethoven, burned to the bone by the African sun." Besides Ellington, 'Doc' Cook was mentor, guide, and/or adviser to countless American artists: among them were Eva Jessye, music educator and original choir mistress for Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, and Virgil Thomson's Four Saints in Three Acts, and the composer Harold Arlen. Cook is the central character in Josef Škvorecký's historical novel Dvořák in Love, and articles and radio broadcasts spring up every time he is rediscovered.